On 27 November, Cyclonic Storm Ditwah struck Sri Lanka with strong winds and very heavy rainfall, causing the worst flooding and landslides since the early 2000s (UN News, 2025). Cyclonic Storm Ditwah became the deadliest weather-related disaster since the 2004 tsunami. Meanwhile Indonesia, Malaysia and southern Thailand were experiencing persistent heavy rainfall, intensified by Cyclonic Storm Senyar that made landfall on Indonesia and Malaysia on 26 and 27 November.

In Sri Lanka, as of December 8, at least 635 fatalities, 192 missing and over 600,000 families displaced are reported; 2.1 million individuals have overall been affected (DMC, Sri Lanka, 2025). For Indonesia, at least 593 fatalities, 468 missing and 2,600 injured individuals as well as 600,000 displaced people have been reported by the IFRC as of December 2, while in Malaysia at least 37,000 people have been affected by the rains (OCHA, 2025).

In Sri Lanka, transport and energy infrastructure have been impaired across the country with at least 247km of major roads and 35 bridges damaged and over 277,000 buildings inundated (ECHO, 2025; DMC Sri Lanka, 2025; News.lk, 2025). Access to clean water remains a major concern (UN News, 2025). In Indonesia, at least 1.5 million people are affected in total, with Sumatra being the hardest-hit region (ECHO, 2025; CNN, 2025).

The influence of climate change on tropical cyclones is rather complex. However, while both regions were hit by tropical cyclones, the impacts mainly stem from the associated heavy rainfall rather than the high winds. Sea surface temperatures and two large modes of natural variability – the ongoing La Niña and the current negative phase of the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) potentially influence the heavy rainfall as well.

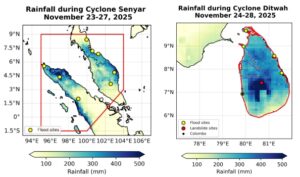

Scientists from Sri Lanka, Philippines, Malaysia, United Kingdom, United States, Sweden, Ireland and the Netherlands collaborated to assess to what extent human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the heavy rainfall in the region. For the assessment of the role of climate change in the heavy rainfall, we study the heaviest 5-day rainfall periods over two domains; Sri Lanka and a region encompassing half of Sumatra and most of the Malaysian peninsula (fig 1), also in the context of La Niña and IOD. To put this in context we also analyse surrounding sea surface temperatures.

Main findings

- Sri Lanka’s flood risk stems from its steep central highlands and low-lying coastal plains. Intense rainfall quickly channelled runoff from the hills into densely populated floodplains. In the Malacca Strait region, the land is shaped by its vast archipelago of volcanic islands, broad plains, and deltas. With many islands having limited natural drainage, and deep valleys, heavy rainfall easily triggers both flash floods and landslides.

- In addition to climate change, extreme rainfall in this region is known to be influenced by ENSO and Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD). Therefore we first check whether these recurring climate variability patterns play a role. For the Strait of Malacca the occurrence of La Niña and a negative IOD this year, which both tend to enhance rainfall in this region, contributed to making the event more intense. We estimate that the current La Niña and negative IOD conditions contributed about 5% to 13% to observed rainfall.

- To estimate if human induced climate change influenced heavy rainfall over the Sri Lanka and the Malacca Strait regions we first determine if there is a trend in observations in the heaviest 5-day rainfall events. The extreme rainfall associated with Cyclonic Storm Senyar over Malacca Strait corresponds to roughly a 1-in-70-year event in today’s climate. Over Sri Lanka, the extreme rainfall associated with Cyclonic Storm Ditwah corresponds to roughly a 1-in-30-year event in today’s climate. Local return periods can be much higher.

- To assess the role of climate change, we first examine whether there is a trend in the observations associated with the warming up until today of 1.3°C. Although different observations-based datasets show a wide range of trends, they all agree on the direction of change, suggesting that extreme rainfall spells are becoming more intense, in both study regions. For the Malacca Strait region, the increase in extreme rainfall associated with rising GMST is estimated at about 9% to 50%. Over Sri Lanka, the trends are even stronger; heavy 5 day precipitation events, such as those associated with Cyclonic Storm Ditwah, are now about 28% to 160% more intense due to the warming to date.

- To determine whether the observed trends can be attributed to human-driven climate change, we also assess high-resolution climate models that are known to capture rainfall patterns in the study regions best. However, models are not good at simulating the seasonal cycle over these small island regions, and the majority also do not capture the correlation with La Niña or the IOD. Over both study regions, these models do not show consistent results regarding the direction of change, so there are probably aspects of the atmospheric circulation that are systematically misrepresented by the models. This is surprising, given the substantial body of scientific literature reporting increases in heavy rainfall both within our study region and across the broader area.

- The large trend that is visible in the observations in both study regions is not captured in the models. This prevents us, without further detailed assessment of underlying processes and their representation in the climate models, to draw an overarching attribution conclusion that quantifies the influence of climate change on these events.

- Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the North Indian Ocean were observed to be about 0.2°C higher than 1991-2020 average, which will have added to the energy available for tropical storm development and evaporation leading to the heavy rainfall. Without the trend related to the 1.3°C rise in global temperatures, the SSTs would have been about one degree colder and below the 1991-2020 normal.

- Across both countries, rapid urbanization, large concentrations of people and assets in low‑lying floodplains and deltas, and infrastructure built in or near frequently flooded corridors have elevated exposure to flood events.

- Cascading failures of transport, energy, communications, and basic services disproportionately affected low-income and marginalized groups, who are more likely to live in informal or substandard housing and to lack savings or insurance.

- While early warnings were issued in both Sri Lanka and Indonesia, failures in ICT infrastructure may have prevented them from reaching intended audiences, and even those who did receive warnings were often unable to anticipate the scale of the floods. Issues such as language barriers, timing of floods, and the remoteness of some communities presented further challenges.