Since late December 2025, severe flooding has affected large parts of Mozambique, Eswatini, northeastern South Africa and Zimbabwe, killing more than 200 people (Al Jazeera, 2026), destroying more than 173,000 acres of crops (Sky News, 2026) and causing further widespread humanitarian and socioeconomic impacts in the affected countries. In Mozambique, more than 75,000 people across six provinces have been affected, with the number rising rapidly as rivers overflowed and communities were inundated. The floods have resulted in loss of life, destruction of over 70,000 homes, damage to health facilities and schools, and disruption of approximately 5,000 km of roads, including the main national highway (N1), isolating Gaza province. Livelihoods have been severely undermined, with over 105,000 hectares of agricultural land and 34,000 livestock lost, compounding vulnerability in areas already affected by the 2023/2024 drought.

The flooding was caused by exceptionally heavy and persistent rainfall across a large region in southeastern Africa starting on December 26th and intensifying from early January, with some areas recording more than 200 mm of rain within 24 hours. Mozambique’s downstream location within major regional river basins, combined with high-volume releases from upstream dams, further exacerbated and prolonged flooding in downstream areas.

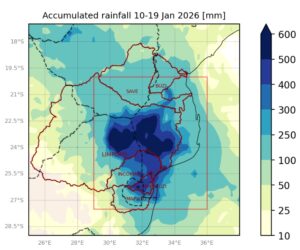

Researchers from Mozambique, South Africa, the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark, the United States, and the United Kingdom collaborated to assess the extent to which human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the heavy rainfall event. To capture the range of impacts from the persistent rainfall affecting parts of Mozambique, South Africa, Eswatini, and Zimbabwe (27.5–20°S, 29–6°E; box in Fig. 1), we analyse 10-day maximum rainfall accumulations (Rx10day) during the December–February (DJF) season. This period represents the primary rainfall season in the region, when dominant rainfall-generating mechanisms are broadly similar and strongly influenced by El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). The spatial domain focuses on a climatologically homogeneous region encompassing the major river catchments—Limpopo, Umbeluzi, Maputo, Incomati, Save, and Buzi—as well as the areas most severely affected by flooding.

Main Findings

- The floods exposed deep and persistent social vulnerability in the region. Recurrent flooding and other natural hazards have trapped rural communities in the lower Limpopo River basin in a cycle of poverty. As a result, flood impacts are disproportionately severe for low-income and marginalized communities. A large proportion of the urban population living in conditions of informality, is particularly vulnerable to flooding, exacerbated by rapid urban expansion, inadequate planning, and insufficient provision of basic services. Poor housing quality and inadequate infrastructure significantly increase exposure and vulnerability to flooding.

- Historical mining practices, weak environmental regulation, and limited awareness of long-term impacts have entrenched persistent and severe damage to aquatic ecosystems which, in combination with long term low investment and low maintenance of aging infrastructure increased exposure dramatically.

- Flooding disproportionately harms vulnerable groups not simply through exposure, but by disrupting life-sustaining systems. Elderly people, persons with disabilities, and people living with HIV face heightened risks as floods damage health facilities, destroy medical supplies and cold-chain infrastructure, and cut off access to clinics, interrupting essential HIV and TB treatment and leading to long-term health complications beyond the flood event itself.

- Pre-existing food insecurity, driven by droughts and other hazards, will be sharply amplified by the floods affecting highly exposed agricultural communities in Mozambique and Eswatini.

- To estimate if human induced climate change influenced heavy rainfall over the region we first determine if there is a trend in observations in the heaviest 10-day rainfall, finding that while the event is with a return period of about 50 years, relatively rare, even in today’s climate that has warmed by 1.3°C, it would have been much rarer in a 1.3°C colder climate. Similarly, all observational datasets show that extreme rainfall spells are becoming more intense, by about 40%.

- In addition to climate change, extreme rainfall in this region is known to be influenced by ENSO. We find that the current phase of ENSO, a weak La Niña during the DJF season, increased the chances and severity of heavy rainfall. Our best estimates indicate that La Niña made such extreme 10-day precipitation more likely, by a factor of about 5 and increased 10-day intensity by about 22%. Thus, the effect of La Niña is about half as the effect of global warming.

- To assess to what extent the observed change can be attributed to human-induced climate change, we typically combine the observations with climate models. However, the models have limitations in this region and do not adequately capture the ENSO correlation. As a result, we cannot confidently attribute the magnitude of the observed change to climate change. However, we have confidence that climate change has increased both the likelihood and the intensity of the 10-day rainfall, based on the observed signal, physical understanding and existing literature.

- Flood policies exist across the region but are inconsistently implemented, limiting their effectiveness. Rapid urbanisation, resource constraints, and gaps in community-level preparedness leave many areas exposed to severe flooding. Strengthening flood resilience will require fully operationalising existing policies, as well as enhancing coordination across river basins, investing in local infrastructure and early warning systems, and building community capacity to prepare for, respond to, and recover from flood events.

- Compound hazards, such as when severe drought periods are interrupted by intense rainfall, cyclone or flooding events leave communities with low capacity to absorb the impact, or build coping strategies. Impacts from flooding such as livelihoods being disrupted – coupled with damage to homes and reduced access to healthcare – can also trigger a number of cascading risks such as disease outbreaks, critical system collapse and further displacement with heightened levels of inequity. Building community-level resilience to these compound and cascading risks is complex, requiring long-term, locally led adaptation that is also embedded within district, national, and regional strategies.