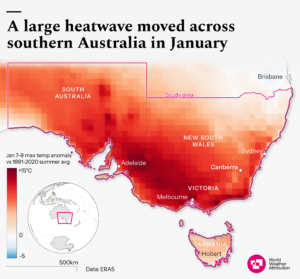

From 5–10 January, 2026, south-eastern Australia experienced its most severe heatwave since 2019–20. Temperatures exceeded 40°C in major cities including Melbourne and Sydney, with even hotter conditions across regional Victoria and New South Wales. Extreme heat affected large parts of Australia, including Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania before moving east to New Zealand.

The heatwave led to widespread health impacts, increased pressure on hospitals, dangerous fire weather, and significant impacts on wildlife. From Friday the 9th of January, the passage of a cold front accompanied by strong winds affecting Victoria and New South Wales, created highly dangerous fire weather conditions comparable to those preceding the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires (AA, 2026), posing more threats on human and animal health, as well as infrastructure. The impacts from extreme heat alone remain substantial, in particular with respect to physical and mental health and led to a surge in heat-related illnesses, with a 25% increase in emergencies in Melbourne (ABC, 2026).

Researchers from Australia, New Zealand, Sweden, Denmark, the United States, the Netherlands, Ireland and the United Kingdom collaborated to assess to what extent human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the extreme heat in the region. The analysis focuses on the 3 hottest days over the most affected area in South Eastern Australia (blue outline, Figure 1), and additional analysis of weather station data in highly populated areas.

Main Findings

- Heatwaves cause more deaths in Australia than all other natural hazards combined. They are already placing acute pressure on Australia’s health system, with impacts extending beyond physical illness. During recent heat events, emergency departments in Melbourne and Sydney reported sharp increases in the number of patients, particularly among elderly people, those living in overheated buildings without access to cooling, outdoor workers, and individuals with pre-existing conditions. In regional South Australia, clinicians also reported worsening mental health presentations linked to extreme heat.

- Vulnerability to heat has shifted over time, from primarily elderly people living alone to populations facing socioeconomic disadvantage and chronic illness, including homeless people and migrants, highlighting the need for adaptive, equity-focused heat-health policies.

- The extreme heat, strong winds, and unusually dry conditions in Victoria in late 2025 combined to create extreme fire weather conditions across a large area which resulted in multiple large, fast-spreading wildfires. These conditions make wildfires very difficult to control, and increase the likelihood of property destruction and deaths.

- This heatwave was the most severe in six years. The 3-day maximum temperatures in the study region observed in 2026 have a return time of about 5 years in today’s climate, which has warmed globally by 1.3°C.

- When combining the observation-based analysis with climate models to quantify the role of climate change in the 3-day heat event, we conclude that climate change made the extreme heat about 1.6°C hotter. While the discrepancy between observations and models is smaller in this region than in other parts of the world, climate models still show a systematically smaller change in likelihood and intensity than observation based assessments. Based on the available evidence we conclude that similar events are about 5 times more likely to occur now than they would have been in a preindustrial climate without human-caused warming; however, this is likely an underestimate.

- After a further 1.3°C of global warming – the level projected to be reached by the end of the century under current policies – the likelihood and intensity of such events are projected to continue to increase, becoming 1.5°C warmer and a further 3 times as likely.

- We further assess the influence of natural modes of variability, such as ENSO and the IOD on the likelihood and intensity of the event in the study region. We find that while the IOD does have a small influence, the current phase of ENSO, a weak La Niña before the summer, reduced the chances and severity of this heatwave. Our best estimates indicate that La Niña made such extreme temperatures less likely, by roughly 20–45 per cent and lowered 3-day maximum temperatures by about 0.3–0.5°C. While natural climate variability reduced the likelihood of this heatwave, the increase in risk driven by climate change is much larger and ultimately dominant.

- The heat experienced in New Zealand’s North Island was a one-in-five-year event in today’s climate. Without human-induced climate change, such temperatures would have been much rarer. Given the affected population is not well adapted to heat, and no heat alerts were in place, severe impacts on vulnerable populations are expected.

- Despite Australia’s advanced warning systems, many people, particularly elderly and vulnerable populations do not recall heatwave alerts or act on them. With strong evidence showing that risk awareness influences behavioural response, there is the need for targeted, impact-based communication to translate warnings into effective risk reduction, including media reporting that avoids stereotypical imagery that downplays risk (e.g. beach and ice-cream images).

- Record daytime electricity demand was met more smoothly than in past heatwaves, largely due to abundant renewable generation. Solar power alone supplied over 60% of midday electricity, and even more when combined with wind and hydro, helping to keep prices stable. This contrasts sharply with earlier heatwaves, when coal and gas plants struggled to meet demand.

- Heat impacts are often most severe in cities, where geography and the urban heat-island effect intensify temperatures, especially in neighbourhoods with high concentrations of vulnerable populations that face additional indoor heat that surpass health safety levels for several consecutive days during heat events. While progress has been made on heat-resilient urban design, it remains a critical priority as people are pushed beyond their coping abilities. At the same time, it is important not to focus exclusively on cities: significant heat impacts also occur beyond urban areas, particularly in rural areas among Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal communities, where risks are frequently under-recognised.