The 2024 long rains in East Africa were exceptionally heavy towards the end of March and throughout April into May, causing severe flooding in Kenya, Tanzania, Burundi and other parts of the region.

Hundreds of people lost their lives in the floods and more than 700,000 were affected by the floods across all countries due to infrastructure damages, school closures, lost livestock and thousands of hectares of damaged crops.

Researchers from Kenya, the Netherlands, Germany, Sweden, Denmark and the United Kingdom collaborated to assess to what extent human-induced climate change altered the likelihood and intensity of the rainfall that led to the severe flooding in the most affected region.

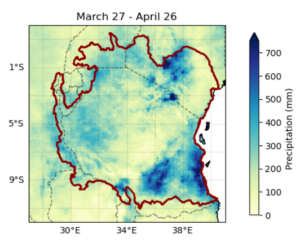

The impacts were most severe in the region around Lake Tanganyika, Lake Victoria, the central Highlands (including Nairobi), southeast lowlands of Kenya and coastal Tanzania between the end of March and most of April. To capture this event we looked at the 30-day maximum accumulated rainfall during the long rains (March to May) in the area outlined in red in Figure 1.

Main findings

- Countries in East Africa have been facing disaster after disaster, including prolonged drought between 2020-23, and multiple episodes of torrential rainfall leading to severe flooding. These disasters combine to create a complex humanitarian emergency that includes displacement, infrastructure loss, food insecurity, health risks, disrupted livelihoods, and overall weakened resilience.

- Rapid urbanisation in cities across East Africa is amplifying flood risks, especially in large informal areas that are located on flood-prone land, lack adequate structural protections from the rains, and whose residents lack resources to recover and rebuild. Land-use changes, including deforestation and conversion to agricultural land are also occurring to different degrees in each of the countries studied, adding to flood risk.

- The East African long rains were observed to show a drying trend towards the end of the 20th century, while climate models projected an increase in heavy rainfall with global warming. While this so-called East Africa Paradox is not as pronounced anymore, with observed precipitation increasing and a new generation of climate models showing weaker or no wettening trend, interpreting observations and climate models is still challenging in this region.

- The observations, independent of the exact region and data product, do not show a long term trend, but instead a drying trend towards the end of 20th century up until around 2008 and a wettening in the last 15 years. Regardless of whether the recent recovery is being enhanced by human-induced climate change, the increased precipitation does bring an increased risk of flooding to the region.

- To understand if human-induced climate change is indeed playing a role, we also assess whether there are wettening or drying trends in the region for the long rains in climate models. While the trends are not statistically significant, they do show a wettening. On average, an event like this has become about twice as likely and 5% more intense in today’s climate, representing the effect of 1.2C of global warming.

- Looking at the future, for a climate 2°C warmer than in preindustrial times, models suggest that rainfall intensity and likelihood will increase further.

- We also examined whether the current phase of the El Nino Southern Oscillation or the Indian Ocean Dipole played a role in the intensity and likelihood of the wet March-May rainy season. Both modes of natural climate variability have been found to exhibit a negligible influence on the 2024 long rains in the study region.

- Taking these findings and the known physical relationship that heavy rainfall is expected to increase in a warming world, we conclude that the observed increase in rainfall in the region over the last 15 years is in part driven by human-induced climate change.

- Therefore, investing in flood resilience with future warming is paramount.

- While early warning systems in each of the countries exist and warn of extreme rainfall, there is room to expand the action taken based on warnings to adequately protect people from the rainfall impacts. Social protection programs can fill gaps in instances where it’s not possible to avoid all impacts, in order to help people recover their assets and livelihoods after the disaster.

- Disaster preparedness policies, flood preparedness and protection infrastructure, and early warning systems that are in place across Kenya, Tanzania and Burundi are all steps in the right direction, but must be integrated and implemented at scale in order to reduce impacts.